Evaluating the CET Theatres Based on Latour’s Questionnaire

Divadlo Husa na provázku theatre’s Pandemic Cabaret (authors: Tereza Holá, Hynek Skoták); theatre’s actors lift a heart statue; photo by Jakub Podešva.

In early January 2021, a series of experimental workshops took place at Brno’s Centre for Experimental Theatre (CET). Designed to reflect the situation of the pandemic, they were based on the internationally circulated questionnaire created by French sociologist and philosopher of science Bruno Latour in June 2020. Attended by three groups of representatives from the three theatres that comprise CET [Divadlo Husa na provázku theatre, HaDivadlo theatre and Terén platform for performative arts, ed. note] , the workshops were led by philosopher Alice Koubová. They were attended by dramaturgs, actors, stage managers, lighting technicians, producers, secretaries, artistic directors, ushers, theatre managers and sound engineers and observed by the CEDIT editorial staff.

Each workshop consisted of a three-hour meeting with a group from an individual theatre. The aim was to create a working environment that was safe and relaxed, but also clearly defined and conducive to individual reflection and subsequent collective debate on topics emerging from the everyday experiences of theatre-makers under the pandemic regulations.

Although each meeting began with a presentation of the context of Latour’s work and his motivations for writing the questionnaire, the workshops did not have to be conducted strictly according to Latour or the suggestions his questionnaire offers. Rather, workshop participants were invited to use the questionnaire as they saw fit to make it as beneficial as possible for the individual theatre groups and their ongoing collaboration.

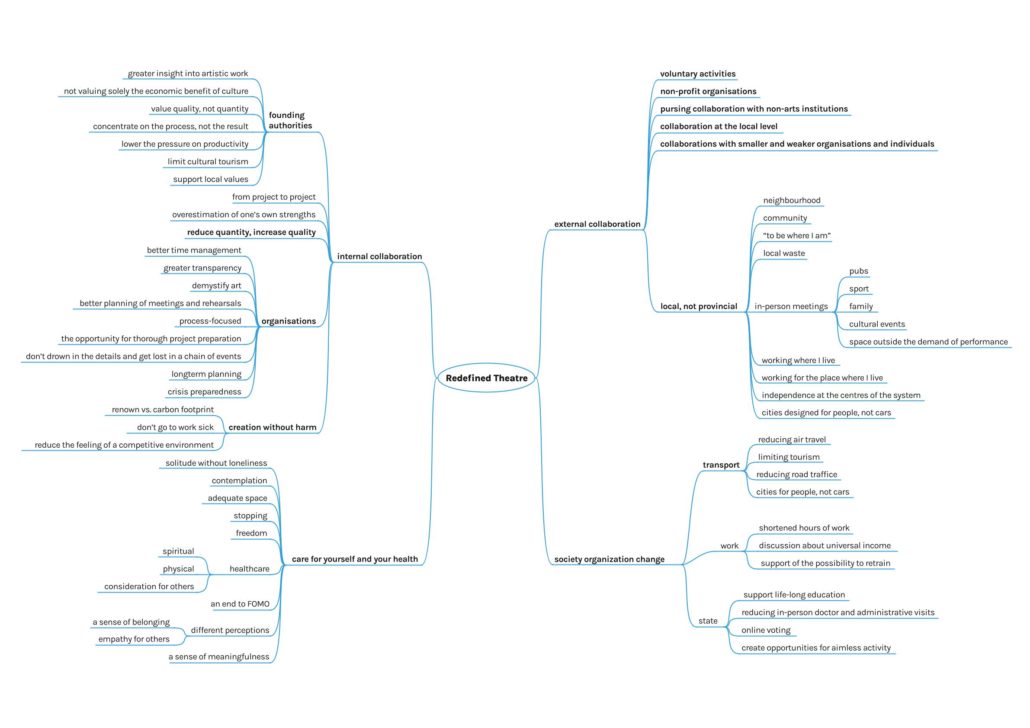

In each meeting, the reflection process began with quiet, individual work with the questions posed by Latour. The desired result was not a completed questionnaire ready for submission. Instead, the intention was to create a moment for individual thinking and self-awareness. Individual responses did not need to be published, but could give rise to ideas for the collective part of the workshop that followed. During the joint discussion, participants created mind maps based on their previous individual work. Here, they could see how their individual topics overlap, amplify, complement, connect and intersect with one another. A virtual mind map was produced after the fact for a group that had to complete the workshop online due to quarantine.

In addition to the work undertaken deliberately, the workshops produced many unintentional ideas, exchanges of opinion and general reflections, which can also be considered an outcome, along with the individual reflections and mind maps.

Coming Down to Earth with Bruno Latour

A prominent intellectual activist, Bruno Latour has long traversed disciplinary boundaries in his work. Early in his career, he questioned how scientific knowledge is formed. Through sociological research, he revealed that what is considered true in science depends on the cultural and social contexts. He noted that the sciences are strongly embedded in the cultural preconditions of a given society, not only in terms of what the society wants to discover and is interested in, but also according to how scientific work is structured and what kinds of scientific work the given society rewards. Latour’s goal was to show that there is no objective science that provides “hard” facts, as opposed to the results of the “soft” social sciences. Following philosopher Michel Serres, he pointed out identical procedures in literature, the sciences and philosophy to show that science also contributes to the creation of the world, not just to its description, and that its methodology also includes “soft” decision-making, etc.

Latour subsequently developed the Actor-Network Theory, according to which reality is perceived as a network of links between “actors” of all kinds: humans, non-human living creatures, organisations, events, objects and environments. According to this theory, in our world meaning is not only created by humans, but also through compositions, in which all actors intervene equally.

Latour does not want to call scientific thinking into question; on the contrary, he wants to show that scientific truth manifests itself as a social force and that it is necessary to share it and to publicly discuss and communicate it in the context in which it has been embedded from the outset. According to Latour, scientific facts become facts precisely and only within a shared culture. Facts of any kind have a material, interactive and emotional dimension that needs to be acknowledged and dealt with. Latour’s activities thus regularly combine scientific research with artistic creation and philosophical or sociological reflection. He is the co-author of five theatrical productions and the curator of several exhibitions in collaboration with visual artists and scientists (see Iconoclash, Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy). Latour also founded the “political arts” as a field of study at Sciences Po in Paris, creating a space where students of art, the social and natural sciences and economics could all study. Together, they collaborate on topics that affect our society and the planet. In recent years, Latour’s attention has turned to a single topic: climate collapse.

The ideas in his text “What protective measures can you think of so we don’t go back to the pre-crisis production model” relate directly to the book Down to Earth, recently published in Czech translation. In this book, Latour emphasises what is a key idea for us: reconnecting science with culture. He writes: “No attested knowledge can stand on its own, as we know very well. Facts remain robust only when they are supported by a common culture, by institutions that can be trusted, by a more or less decent public life, by more or less reliable media. […] It is not a matter of learning how to repair cognitive deficiencies, but rather of how to live in the same world, share the same culture, face up to the same stakes, perceive a landscape that can be explored in concert. Here we find the habitual vice of epistemology, which consists in attributing to intellectual deficits something that is quite simply a deficit in shared practice.”[1] According to Latour, facts — even facts about climate change — will be able to change our lives only when they become part of our shared cultural life, shared practice and shared knowledge of the world. Cultural institutions thus play a key role in this.

In Down to Earth, Latour argues that the solutions to climate change that are offered today swing between two polarised attractors: the Global and the Local. We move between the need to become more global and abandon conservative values and the need to return to a regional orientation with locally relevant values. Intermediate states are lost in the war between polar opposites: Left vs. Right, Globalism vs. Localism. The solutions being fought over in these wars cannot be sustained in the long run, because the polarisation that created them is embedded in their structure. The attractor that interests Latour is the Terrestrial, the Earth, which presupposes the ability to remain on this planet in a network of relevant connections and does not seek a means of escaping from it.

The first principle of how to come “down to earth” is to create unexpected connections and collaborations. However, this is not to make a “virtue of necessity,” or a necessary rational compromise; rather, it is about emotionally processing the fact that working with people outside of my mutual confirmation bubble, whose views may not be in complete alignment with mine, is the only way to come back down to earth.

The second principle that will make it possible to come down to earth is the ability to imagine and accept that some of the things we do in our personal, professional or civic lives are not contributing to coming down to earth. It’s essential to grasp that it’s not just everyone else that’s behaving badly; I am also involved in a system that is destructive in the long run. If we want to reverse the direction of climate collapse, it may be necessary to change some of “our” attitudes, “our” practices and “our” ways of earning money, even those in which we have a strong emotional investment.

To help find his way down to earth, Latour created a short questionnaire in his text of June 2020. It encourages individuals to write out their individual experiences resulting from the pandemic and leads them through deeper processing aided by specific questions. At the same time, Latour emphasises the need to start with one’s own experience (however small and insignificant it seems from a global point of view) as a starting point that can be developed and contribute to the process of drawing more general conclusions.

This approach is based on the experience of the so-called list of grievances (cahier de doléances), which had a major impact on the course of the French Revolution. At a time when the power of the absolutist establishment was under threat, but not yet defeated, members of the Third Estates — citizens not yet visible on the political spectrum — drew up lists of complaints describing their everyday problems, needs and difficulties. The massive volume of these notes, the power of their specificity and the surprise of a voice coming from a previously silent part of society, contributed to the subsequent fall of the absolutist regime in France.

Latour was inspired by this story and suggests writing similar notebooks of complaint as a strategy for the present. He places the greatest emphasis on the willingness of individuals to write down their own specific experiences from the pandemic period. Only after writing one’s individual testimonies and reflections is it appropriate to move up a level and share your discoveries in a group, looking for points of overlap, intersection and amplification. A huge number of individual responses are the only basis from which it will be possible to consider creating a more general document and harnessing political power.

[1]LATOUR, Bruno. Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climate Regime. Cambridge, UK, Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2018, pp 46, 50 (e-book edition)

Methodological Observations from the CET Evaluation

Barbora Liška: Responsibility as Gaming Principle

I think that the difficulty of working with the Latour questionnaire lies primarily in the fact that Latour thinks about his questions consistently; he implicitly offers the opportunity to invent a whole new social and political order, another world in all of its complexity. There was someone in each of the three groups who reflected on this fact and it was this potential hidden in the questionnaire that caused me the greatest problems in answering the questions. Thus, I’ve tried to uncover what exactly it was that caused my hesitation and to think about how to approach the questionnaire so that it would be beneficial to me and my self-reflection.

Although Latour asks very specific questions and emphasises the respondent’s subjective point of view, any answer to the question of what activities should and should not be resumed after the pandemic is necessarily caught in a network of very complex circumstances. With the globalised and interconnected state of the world, any concrete proposal to change the system inevitably leads to questions: “What else needs to be considered in order for this change to ever become a reality?” “What have I forgotten that impacts the current arrangement and do I need to take it into account in the alternative activity I’m proposing?” This intense awareness of complexity can cause us to doubt whether anything better can be found at all, which is absolutely fair and includes no catch that could lead us to disaster. The sense of one’s smallness in relation to the system in which one lives can also (but of course does not have to) block the respondent in their attempt to answer.

Responding to Latour’s questionnaire is very strongly linked to a willingness to accept responsibility for others. If someone feels this particularly intensely, wants to be as fair as possible and does not want to cause anyone harm, they may lose the courage to answer at all. Still, I came up with three principles for coming to grips with the unpleasant feeling of being responsible for everything — good and evil.

I think it’s important to approach the questionnaire a bit like a game, to engage the imagination and leave more room for creativity and the space to simply imagine how it would be nice “if…” To accept the role of “simpleton” instead of “international politician.”

To be playable, a game needs clearly defined parameters. It is therefore good, I think, to set up this creative approach as a framework in advance. The first response doesn’t have to be at the level of the whole of Czech society, the whole of Europe, or the whole world, but perhaps can just concern me and my affairs, my immediate family as a community, my collective at work. When we consider these narrower circles, our closest spheres of influence, it is much easier to come up with specific measures and imagine that the proposed changes constitute another reality that is possible, specific and not abstract.

However, in my opinion, the most important “game” principle of Latour’s questionnaire is taking responsibility for the proposed changes in relation to oneself. The key is to ask yourself questions: Am I personally willing to sacrifice what I would like to abolish and accept the alternative I am proposing? Or am I excluding myself from the impact of the change and, in fact, mostly suggesting that others change? Can I imagine myself in new conditions and adapt? We often have more influence on change in our closest communities than we think and the biggest advantage is that the agreement to implement a new system depends on just a few people.

Jakub Liška: A Performance Based on Latour?

When I read the English translation of Latour’s essay, I got the feeling that I could not do it, that answering his questions would be too difficult for me.

Only when I was literally forced to work with the questionnaire in the workshop and answering was a pressing demand, rather than a possibility, did the question arise: From what position am I answering? As the editor of a theatre magazine, a doctoral student at Masaryk University or an individual named Jakub Liška, who tells a certain story about his life? Even during the discussions with the individual theatres, it was mentioned that it is very difficult to respond to the questionnaire if the respondent is not clear about these things in advance: “who they are,” “for whom they speak,” “from what position they speak,” and “what should be done.”

In the first phase, the questionnaire prompts one to reflect on themselves and their position. Latour sets a higher bar for subsequent responses; he doesn’t want respondents to think only for themselves, but also asks them to place themselves in the position of others and to think as if they are in those people’s situation. But, as one of the workshop participants remarked, “How can I think for someone else when I don’t even know what to do myself?” Perhaps some acting techniques used to create characters have been addressing this question for a long time.

Some participants responded to the invitation for self-reflection to reflect on their feelings, which in turn gave rise to formulations of specific activities. An awareness of my own situation, experiencing the feelings I have about it and developing them into actions, the magical “if”… These strike me as approaches that are quite close to some acting techniques and engaging with the questionnaire does offer a lot of space for acting methods. In fact, the questionnaire could easily serve as an impetus for the creation of a performance.

I think that such a use of Latour’s questionnaire is a good fit for the theatre’s creative potential. As the dramaturgs at the workshop noted, Latour’s language is still “pre-crisis.” He still uses the division of “us” and “them” and takes sides himself. Theatre, however, could overcome this ideology and find its own use for his questions in a direct re-action, whether in the form of a theatrical performance or another event.

Alice Koubová: A Different Way to Connect with Others

From the reactions of the participants, it seemed to me that a workshop like this was valuable because it also made it possible to create time and space for the working groups to gather around a topic that was important to everyone but did not concern pressing operational matters. The participants mentioned that it was valuable to meet and think together about something that was neither a specific, urgent theatrical problem, nor a relaxed meeting over a beer, but an encounter that stimulates thinking and debate and deals with the issues impacting theatre in a broader context. Perhaps such meetings can even give rise to unusual ideas for the theatres’ future creative work.

It was interesting to watch individual participants’ surprise at how closely their answers mirrored those of others. In my opinion, this experience, where individuals formulate their personal observations and then find out that they are not alone in them, carries an important resonance. It’s as if they experience their presence in the group even more strongly, that they are there as themselves, with personal attitudes that are no longer pre-adapted to accommodate the interests of the whole. Despite this, concern was expressed during the group work that even though almost everyone agreed that aspects of their work did not suit them and were happy to have had that revelation, they were unsure if it would really be possible to change these things in practice. It would be interesting to identify the source of this pressure to do things in a different way than everyone would like and to perhaps focus some interventions there.

I was struck by how difficult it was for some respondents to formulate an individual list of grievances, as if they felt these were not relevant and needed to be conceived a bit more abstractly in order to be communicated to the group. Still, individual observations and specific suggestions had great resonance, for example: “every day I observe some small progress in my life;” “I don’t want to go to work when I’m a little sick any more;” and “I would like to meet other people in my specific field and learn something from each other.”

Evaluating the Mind Map: A Changed Theatre

Drawing on the theatre staff’s descriptions of their individual situations, we abstracted ideas and specific suggestions for transforming the system into a mind map. This infographic has, of course, been created with a great deal of idealism and imagination and takes into account the fact that the consequences of individual points have not been fully thought out. Still, a concrete proposal is the first step in thinking towards change. Some visions may never be fulfilled, but others can be implemented now. All the proposals and ideas, however, are united by the fact that they can at least be considered in relation to our own lifestyles.

MIND MAP

External Collaboration

It seems that the pandemic restrictions on movement have made it possible to focus on the relationship between ourselves and the environment in which we live and work and to rethink the potential of our local impact. All three theatres stressed the need to form diverse alliances of smaller institutions and to establish cooperation not only across artistic disciplines, but also with non-artistic institutions from the non-profit sector that share the artistic institution’s values. Creating a mutual support network can be beneficial both in the event of potential future crises and in the post-pandemic moment, when it may be more necessary than ever to defend the significance and importance of culture for a healthy, humane community.

International and intercity collaboration between theatres through touring, which is a major criterion of evaluation in the eyes of the establishing authority, emerged as a topic for debate and reconsideration. The theatres questioned whether this activity has other benefits beyond contributing to their prestige. While they see the potential in building international collaborations, it is clear that they are now more inclined to develop their local activities. They have stopped prioritising “becoming a world-renowned theatre” and are instead thinking about how to become a good local cultural centre that is not provincial and continues to challenge audiences.

The building and development of collaborations with secondary school or university students and exploring educational opportunities through the arts and culture have proven as important as live contact between different institutions.

Social isolation and the necessity to reduce meetings have shown that participants miss the “agora,” i.e., the possibility to have unplanned, spontaneous meetings in a neutral space, such as a pub or cafe, where it is possible to talk about anything and everything, inspire each other, plan and have fun without obligation and outside of clearly demarcated boundaries, which can lead to unexpected topics and ideas.

Ideas, thoughts and practices:

- Think about what items or services I can exchange or share with someone else.

- Take advantage of the impossibility of travel to get better acquainted with the place that I live in and share with others, develop a relationship with it and take care of it.

- Think about the most disadvantaged members of society and take the opportunity to get involved in volunteer activities.

- Offer the theatres’ premises to events of solidarity when performances are not scheduled.

- Offer nonprofit organisations space on the theatre’s billboards.

- Organise non-artistic events, such as lectures and debates, that promote solidarity and civic engagement.

Internal Collaboration

All three theatres reflected on the effects of the pandemic situation on CET’s internal operations. The need for better communication with the founding authority was a strong theme in all discussions.

The theatres would like the founding authority to better understand the specifics of their operation. They do not want to be judged solely on the basis of quantitative indicators such as the number of premieres, the number of spectators or box office receipts.

Theatre staff themselves spoke to an excessive emphasis on performance that is reflected in the high number of premieres and performances, and which sometimes leads them to overestimate their own strength. It is thus not only external pressure from the founding authority, but also the internal set-up of individual teams that is focused on performance. This raised the question of how to change the internal set-up of self-discipline, which takes a negative view on perceived lack of performance.

The pandemic regulations have had a calming effect on operations across the organisation. Some theatres even reflected on the intense, pre-covid mode of operation as having been unbearable for a long time. In the future, they would like to retain the possibility to prepare each project thoroughly and let go of the need for daily performances. There have been various proposals to reduce working hours, such as shortening the working week, introducing longer times for the preparation of productions, etc. At the same time, there is a call for longer-term planning and better use of time in rehearsals and meetings.

All of the theatres also shared a degree of resistance to creative approaches that rely on suffering, martyrdom or self-harm. Each expressed a strong desire for modes of creation and operation that do no harm to theatre staff and called for a creative environment that is considerate to its staff and its surroundings.

Ideas, thoughts and practices:

- Shorten working hours without trying to do the same amount of work in less time.

- Don’t drown in operational concerns and consign deeper thinking to the margins of everyday life.

- Let go of the idea that a person is a hero for coming into work sick.

- Do say, “There’s nothing to catch up with. Let’s go at a different pace.”

- Evaluate culture according to its aesthetic and educational aspects, according to its ability to create subtle collaborations and ties.

- Organise a workshop for representatives from the founding authority to get them better acquainted with the theatres’ operations.

Caring For Yourself and Your Health

Some ideas were directly aimed at taking care of oneself and finding other ways of treating oneself. Many participants spoke about the importance of slowing down their lives and how this led them to develop their own daily practices. What is it like to exist in solitude and not feel alone? What rhythm suits my body? What space does it require?

It turned out that revising their relationships to themselves, including considering their diet, taking care of their bodies, spending more time with themselves, slowing down and paying greater attention to the activities of life brought theatre-makers a sense of freedom. Once one is able to find sufficient nourishment in relationship with themselves through contemplation, daily awareness and the meaning of silence, they also begin to experience another kind of meaningfulness that happens in slow motion and is not located somewhere far ahead of us, in future, unrealised projects. Such meaningfulness in relation to the self also changes our relationships with others. If relationships with others are not the sole confirmation of our value, some of them can be let go of without experiencing loss of meaning. This is the end of FOMO – fear of missing out. Meaningfulness is much closer than we might think.

Practice

- Every day, write down a new success I’ve had, the progress (however small) I’ve made, the ways in which I am richer.

- Perceive those closest to me much more intensely; they are a source of my well-being.

- Transform frenetic participation in a huge number of events into more selective encounters with people who will become part of my life.

- Travel by means other than by car.

- Be able to turn down a commission and save time for something other than work

Reorganising Society

This category was the most general and most imaginative in terms of concrete proposals for realistic action in the context of many other changes.

The ideas that emerged in this category concerned issues of transport, changes to working conditions and the digitisation of administration tasks. Within transport, opportunities were sought to reduce emissions by decreasing air and car traffic; specific ideas included repugnant advertising (similar to that on cigarette packets) and strengthening the appeal of nearby regions, but also the weakening of festival culture and finding new ways to assess the quality of artistic projects, which are not based on how many countries they’ve been performed in. Through a campaign of “cities for people,” we could see more regulations to prevent excessive automobile traffic in urban areas. In terms of restructuring working conditions, proposals were made for a well-thought-out system of retraining and lifelong learning, universal income and a reduction in the number of working days. Many bureaucratic and administrative tasks are suitable for digitisation and could be made more efficient. This is also relevant for the new balance between online and in-person work meetings.

Text: Alice Koubová, Barbora Liška, Jakub Liška

Translation into English: Becka McFadden

The article was originally published in CEDIT 05